A large landowner with several slaves ran a store in southwestern Graves County in the 1820s. Two of his slave girls both wanted the same man and grew jealous of each other. That jealously turned to pure hatred. Tensions boiled over, and the girls agreed to meet in front of the store to fight it out. The winner would claim the man they both coveted.

The girls fought a no-holds-barred battle, bringing knives to cut each other up. When it was over, the they brawled to the death, bleeding out on the dirt road in front of the store. The girls’ names were Flissy and Anna.

That grim moment is one account of how Feliciana, Kentucky received its name.

Unquestionably, that is the darkest version of Feliciana’s namesake. Other variations of the story suggest the two girls didn’t kill each other but was stopped by the store owner. Another version says one killed the other. No matter which outcome, it’s a wild story of how a community began.

There is one historical reference, however far less enthralling, on how Feliciana was born. A man from New Orleans came up and settled in 1820, right after Jackson’s Purchase from the Native Americans. He had two daughters, Felice and Anna, and combined their names when a post office was established in May 1829. This seems more believable, but the truth may never be known.

Feliciana is a classic story of early promise, growth, and demise due to the routing of critical transportation arteries in the 19th century. The community began to prosper in the 1830s and several commercial establishments were built. Two banks, a hotel, several professional offices including doctors, mechanics and craftsmen called the town home – even a racetrack of some sort.

The Bethel Primitive Baptist Church built the first structure in 1825, providing an alternative for the town’s jailhouse and saloon which were also located there.

Official establishment of Feliciana came on February 11, 1834, with incorporation three years later on February 23. The language of the 1834 Act of the Kentucky General Assembly is noteworthy, peeling the layers back of an era that would make modern society cringe:

“… the free male inhabitants of said town of the age of 21 years and upwards…”

The Act went on to state that the citizens (free men over 21) would meet in the house of Levi Calvert on Washington Street annually on the first Monday in May and elect by voice vote five trustees of the town. No women or slaves could take part in the decision-making process, which was common practice for the time.

Feliciana on the Trail of Tears

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 forced Native American tribes to relocate from parts of the southeastern United States to Oklahoma. The pathways and routes taken by Native Americans became known as the Trail of Tears.

John Benge led a group of 1100 Cherokee men, women, and children through Feliciana in the fall of 1838, making their way from Dukedom to Columbus (then known as Columbia). The route follows present-day Old Bethel Church Road to Kentucky 94, through Feliciana and on to Water Valley. Official highway signs designate the Benge Route of the Trail of Tears through southern Graves and Hickman counties.

State Roads Bring Prominence to Feliciana

Not long after the forced migration of Native Americans through Feliciana, the first state road was approved by the Kentucky General Assembly in 1839. The road would travel west to the important trading center of Hickman located on the Mississippi River. The language of the Act states that the road must be 30 feet wide and “stumps in the same cut low and rounded at the tops, and in all respects made so as to administer safe and convenient passage.”

State roads back then were just dirt, no gravel, and contained obstacles like stumps. Certainly, however, better than nothing. That state road is still in use today, although significantly upgraded. Kentucky 94 from Hickman to US 45 traces the original route, as well as Latta Road from US 45 to the site of Feliciana.

One who travels Latta Road can easily see that it’s been around a long time. This seldom-used road, now paved, has not had any right-of-way improvements since it was cut over 180 years ago. The narrow, one-lane road features steep banks and centuries-old trees provides evidence this road is ancient. It’s a beautiful drive.

One year later the General Assembly passed an act extending the road east from Feliciana to Boydsville. Attempting to locate this route today is a little more difficult. It’s possible the old road follows present-day Old Bethel Church Road to near Dukedom, then along the state line to Boydsville. Maps from the 1880s show the road, although today most of it along the state line is abandoned or privately owned.

Other roads were constructed at some point to Columbus on the Mississippi, a strategic shipping point at this time, and to Mayfield, the seat of Graves County. By the 1840s and into the 50s, Feliciana became a relatively major commercial hub in the region, before Mayfield took off and before Fulton was even around.

Feliciana's Decision That Doomed the Town

In the early 1850s, two men traveled to Feliciana, finely dressed, seemingly well-to-do. The suspicious residents of Feliciana soon learned these men were from the New Orleans and Ohio Railroad. They were looking to build a line through Feliciana, connecting the town to a major railroad stretching across the country.

Most of the residents of Feliciana were not impressed and didn’t want anything to do with the railroad. Some were concerned the locomotives running through would kill their cows and horses. Others were concerned about the type of people it would bring through the community and setting off uncontrolled growth. They liked Feliciana the way it was.

The townspeople reportedly voted against the railroad passing through Feliciana and refused to sell rights of way to the railroad. Not wanting to veer far off the planed route from Paducah to Mayfield to Union City, the company located the tracks three miles west of Feliciana and opened the line sometime around 1858.

A railroad stop named Morse Station sprang up where the road from Feliciana to Columbus crossed the new railroad. Soon commerce and subsequently residents began shifting from Feliciana to Morse Station, which would later become Water Valley.

The Civil War Era

The Civil War brought increased activity to Feliciana. Camp Beauregard was established by the Confederacy in the winter of 1861-62 about a mile north of town near the railroad. With Morse Station not as prominent yet, troops visited Feliciana for supplies, including alcohol.

During the Civil War, the town contained four stores, two hotels, a masonic lodge, a school, druggist, four doctors, a lawyer and magistrate, two blacksmiths, a boot and shoe maker, a tanner and two tailors. The town probably enjoyed a brief period of time when the Confederacy destroyed the new railroad through Morse Station, but the railroad was quickly rebuilt.

After the Civil War, the community’s demise accelerated with the local post office closing in 1869. The post office moved to Morse Station to take advantage of the railroad. Not much else is known about the continuing decline of the town through the 19th century. It happened quickly, with one hint from the 1880 Graves County Atlas referring to it as “Old Feliciana”.

Today, all that remains of the former community is less than a dozen modern-day homes, farmland with a couple old country lanes, and a historical marker along Kentucky 94 noting the former town.

Location of Feliciana

Got Information on Feliciana?

If you have any information of Feliciana you’d like to share, please get in touch with us.

Articles Related to Feliciana

Resources

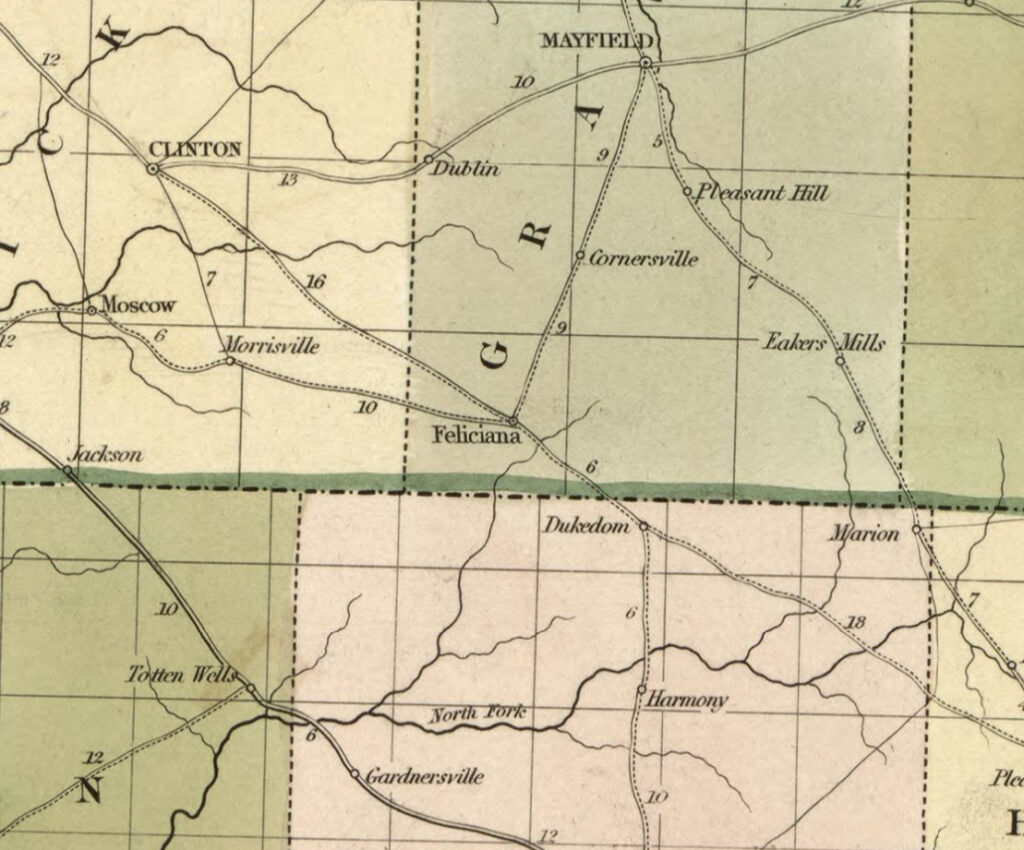

- David Burr’s 1839 Map of Postal Routes

- Kentucky Place Names – Robert Rennick

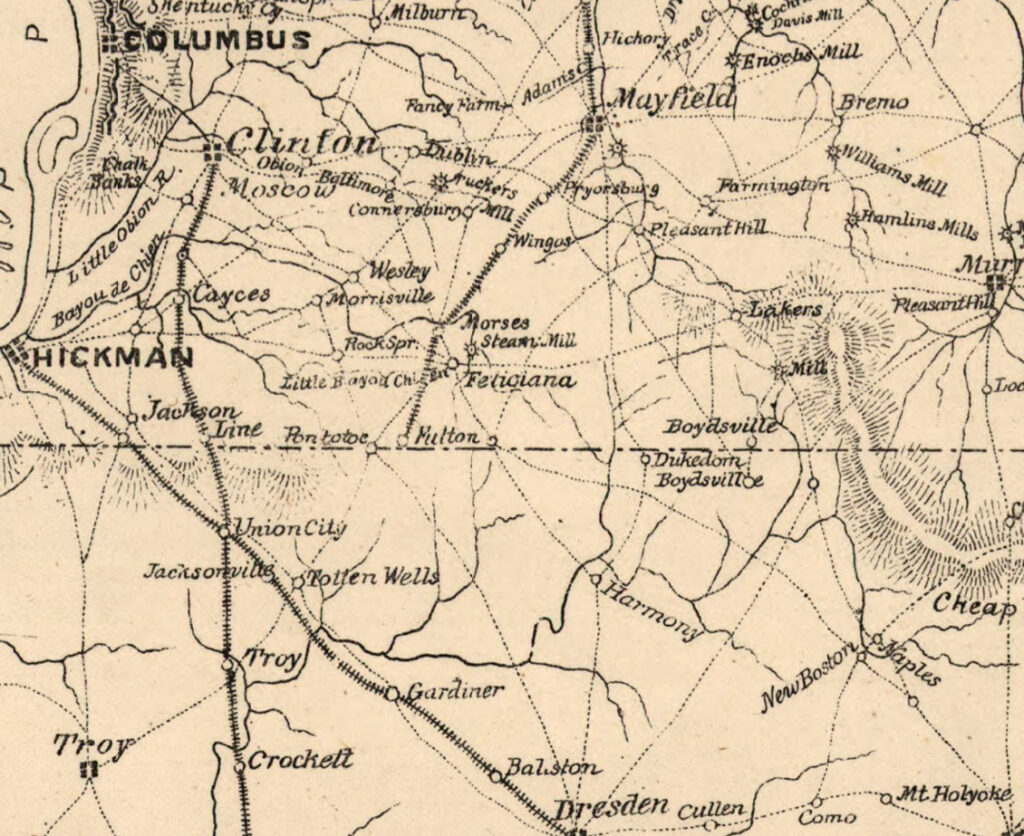

- 1880 Graves County Atlas

- GravesCountyKy.com – History

- Feliciana, South Graves County, Kentucky – Town That Didn’t Want the Railroad – The Paducah Evening Sun – October 27, 1924

- Kentucky Folklore Record – Lon Carter Barton – Published as Place Name Stories About West Kentucky Towns (edited by Violetta Maloney Halpert)

- The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Vol. 61, No. 2, pp. 148-157. – Phillip M. Shelton.

Pingback: Camp Beauregard of Kentucky - Diseased, Depressed & Dystopian - Four Rivers Explorer

Pingback: Wilmington, Kentucky - Four Rivers Explorer