In 1901, William White had a problem. He wanted to bring a railroad to Cadiz, Kentucky from nearby Gracey to help transport tobacco and other freight across the area. Gracey had nice rail lines served by the Illinois Central and the Louisville and Nashville. Connecting Cadiz to Gracey would benefit the citizens of this Trigg County seat immensely.

The problem was rather unusual. In order to be an “official” railroad, a line had to be at least 10 miles. The distance from Cadiz to Gracey was only around 8 miles. So what did White do? He planned to make his railroad 10.33 miles by constructing extra curves. Problem solved.

After incorporating on March 9, 1901, a ground-breaking ceremony was held in Cadiz on April 22. Grading work began soon after and was completed on November 8. Rails were being laid a few days later, beginning at Gracey. The work was back-breaking with one person usually dragging heavy crossties and a small crew of men hauling individual rails to put in place.

The bending, setting and hammering of the rails into the ties was all manual labor. While a few donkeys helped, all the work was done without machinery.

Regardless of the grueling, laborious work and the cold weather the men faced, laying the track carried on through the winter months and the railroad reached Cadiz in March 1902.

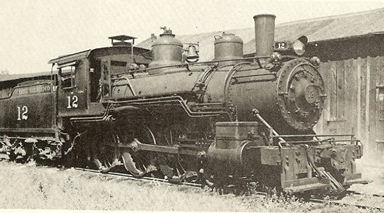

An 1892 Baldwin 4-4-0 was the first locomotive used on the line. Passenger service began with two round trips six days each week. Along the 10.3 miles between the two main towns, the train stopped at Elling Crossing, Montgomery (near where Interstate 24 crosses US 68 today), and Millers Crossing. Five passenger trains served Gracey, so folks from Cadiz and nearby areas were more connected to the outside world than ever before.

Hauling on Dirt Roads

In Trigg County, the Cumberland River (today’s Lake Barkley) was the equivalent of an interstate highway. It was the only way freight could be shipped in large quantities for those who lived in the area. There was a busy ferry and landing at Canton, about nine miles west of Cadiz. But getting there – or anywhere – wasn’t easy.

As the case throughout the country in the early 1900s, getting around by way of road was difficult. In rural areas, poor dirt roads were typically the only available transportation for carrying goods using wagons from one spot to another. Navigating washouts, fording through creeks and climbing steep hills were challenges. And if it rained substantially, you might as well stay home.

Tobacco was a major cash crop for farmers during this era. White, who was a tobacco farmer, knew he could get more money by selling his “Trigg County Leaf” to New York markets, getting double the amount over the nearby markets in Hopkinsville and Clarksville. New York would pay 21 cents per pound, with the local markets only providing 10 cents. At that time, it cost six cents per pound to raise tobacco. With river shipping at Canton unappealing, White built his railroad to Gracey.

Tobacco Wars & The Nightriders

During the construction and for the first few years of the railroad, the price of tobacco fell substantially, even as low as three cents per pound. At that price, profits were not possible.

Tensions began to rise with the cheap buyer-controlled markets. Around 1903, several hundred tobacco farmers joined forces and created the Planters’ Protection Association to combat the buyers. The association’s early diplomatic tactics failed, and they became violet toward those who were not aligned with their mission. These became known as “The Nightriders of the Black Patch” because they did their terrorizing at night.

Much has been documented about these raids that lasted until about 1911. The Nightriders wreaked havoc; destroying crops, burning barns, and beating people were commonplace. Lynches were even documented.

News of the late-night raids spread rapidly throughout the region. Farmers began shipping their tobacco by rail rather than attempting to sell at local markets. The Cadiz Railroad benefited from this, with increased (albeit seasonal) shipments of tobacco across the line to Gracey and on to markets in the northern part of the country.

Isolated incidents of Nightrider attacks on railroad property did occur, especially in the summer of 1908, when the depot at Gracey, Cerulean and Otter Pond were burnt. Sabotages were made on water towers along the main lines as well. But all the Nightrider activity stopped by around 1911 when law enforcement began to crack down.

Tobacco continued to be a major cash crop for the region until the Great Depression.

The Roaring 20s & Passenger Decline

Before World War I, the Cadiz Railroad purchased a gasoline-powered railbus for increased passenger service. Throughout the early 1920s, the line offered four daily roundtrips to Gracey (except Sunday). More than 20,000 passengers rode the line each year. During this time, roads were being planned or developed in the region, with the first state highway under construction through Cadiz to Canton in 1919. Automobiles were not a major competitor yet, since rail offered people the ability to travel great distances.

However, as more roads were being built and cars became more of a dependable mode of transportation, passenger service began to slowly decline. The railbus was retried in 1929 and passenger service was trimmed down to only a single round-trip, powered by the old steam locomotive.

Train ridership continued declining nationwide with more and more highways being built. The Louisville and Nashville Railroad abandoned its line from Princeton Junction, Teen. (near Clarksville) to Gracey in February 1934. The Cadiz Railroad lost is US Postal Service contract in 1941, which was the final nail in the coffin for passenger service along the line.

After tobacco lost its prominence as a significant source of income for the railroad, lumber became the line’s top cargo. The White family owned a lumber mill adjacent to their railroad and they became their biggest client, providing much of the line’s freight. Additional goods were shipped, too, including coal, oil products, pork, cement and other minor freight for the businesses and farmers of Trigg County.

Turning Point

Henry Stanley “Stan” White, grandson of William White, became superintendent in 1954 and president in 1965. By then, business had dwindled down to the point where the White family lumber mill was the only thing keeping the rail line going. Hauling only consisted about five or six carloads during an average week. The business was spending $1.67 for every $1.00 in revenue. The White family knew it was unsustainable.

Stan White was quite active in the community throughout most of his life. In the mid-1960s, White served on the board of the local Chamber of Commerce and played a key role in landing an automotive parts supplier to Cadiz – Hoover Spring (later becoming Johnson Controls, which closed in 2009). Keeping the Cadiz Railroad viable was one of the conditions of bringing the plant to Cadiz.

To help solidify the Cadiz Railroad’s future, the Hoover company purchased a 51% stake in the railroad with the White family continuing to operate. Carloads increased significantly – more than fivefold at one point – with about 70% of rail line’s tonnage coming from the new plant at Cadiz.

Later Years & Abandonment

The Cadiz Railroad continued to hum along through the 1970s until a nationwide recession hit the automotive industry. In 1979, Hoover purchased the remaining stock of the Cadiz Railroad, becoming 100% owner. The line was seeing 50 carloads each week – remarkable for a short line railroad at that time. However, toward the end of that year, Hoover cut production significantly, which meant less cargo for the Cadiz Railroad.

To make matters worse, the Illinois Central Railroad was studying if they should abandon the line from Princeton to Nashville, which was the only connection for the Cadiz Railroad. White began to come up with contingency plans if this were to occur, including leasing the tracks from Gracey to Hopkinsville or Princeton. However, operational costs would increase, and additional revenues were uncertain.

On May 29, 1980, the study was completed and Illinois Central published its abandonment petition for only the Hopkinsville to Nashville line. Gracey would still be served, meaning the Cadiz Railroad would live on.

The automotive industry began to turnaround in late 1981. Hoover began to ramp up production at its Cadiz facility and parts were being shipped once again on the railroad. Things were looking up.

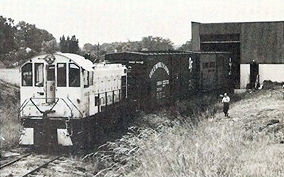

In 1984, Hoover leased the line from Gracey to Princeton, which added an additional 18 miles of trackage to the Cadiz Railroad. However, in 1988, Hoover abandoned the entire line and the rails were removed. The only track that remains of the Cadiz Railroad is a short 20-yard section that supports the last running locomotive of the railroad, a 1941 Alco-GE S1.

Stanley White’s Labor of Love

After serving in World War II, Stan White spent most of his time working on the railroad until his retirement in 1985. White passed away May 1, 2019, just three weeks shy of his 95th birthday. His legacy and contributions to Trigg County are immense. But when he worked on the Cadiz Railroad, it was a labor of love. In an article that ran in the Evansville (IN) Courier-Press in May of 1978, White was quoted saying “if you’re doing something you enjoy, nothing can beat that. I wouldn’t trade jobs with anybody.”

The Cadiz Railroad Today

Railroad and local history enthusiasts can see the old Cadiz Railroad locomotive perched at its final resting spot on US 68 near the Wildcat Chevrolet dealership. The old lettering is still visible as is the engine number – 8.

A 2.5-mile paved hike/bike trail has been established on the former right-of-way from downtown Cadiz. It’s a great place to spend a couple of hours hiking or for a quick bike trip down a 110-year-old rail corridor.

Map

Resources

- Trigg County Historical Society

- Trains Magazine

- The Evansville Courier-Press

- WKMS

- The Nashville Tennessean Magazine

- Historical photos provided by the Trigg County Historical Society/Facebook